For more than a century the automobile has become the preeminent form of transportation. The manufacturing of cars is central to our economy for jobs and also as a driver of resources for them. The use of cars is a choice for some of us and a de facto mode of travelling for many. While the impacts of the cars primacy on the environment, the landscape, our cities and our bodies are still being fully understood, the inevitability of cars in one form another are with us for a while is evident.

For more than a century the automobile has become the preeminent form of transportation. The manufacturing of cars is central to our economy for jobs and also as a driver of resources for them. The use of cars is a choice for some of us and a de facto mode of travelling for many. While the impacts of the cars primacy on the environment, the landscape, our cities and our bodies are still being fully understood, the inevitability of cars in one form another are with us for a while is evident.

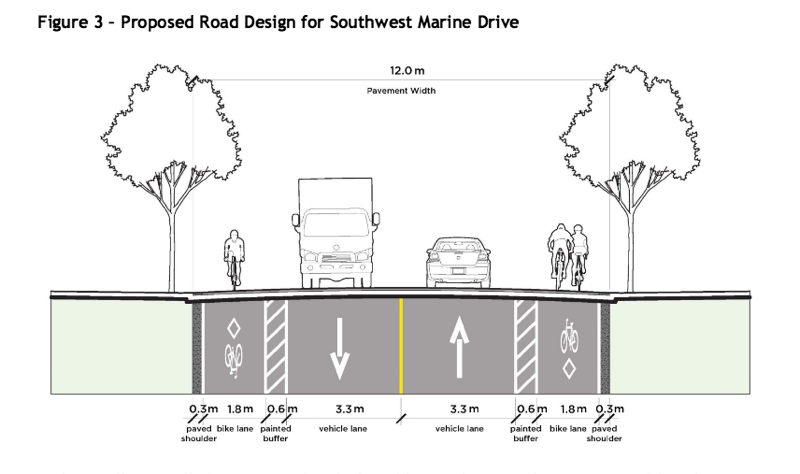

For many reasons the use of private cars has become problematic. From pollution, climate change, personal safety, to a desire to live a more active life style, cars become a transportation choice of last resort or an easy convenience. While the automobile’s dominance has been the past, clearly it won’t always be the only transportation choice in the future. A more complete and complex transportation system needs to be developed that values a multiplicity of types from walking, riding bikes, public transportation, rail, electrical vehicles and who knows maybe even driverless cars.

And while it has taken over century to roll out the primacy of the car it will take a while to transition away from its dominance. Part of this transition process is going to be to understand the histories of the car. With this in mind I have been reading Christopher W. Wells excellent and exciting book Car Country: An Environmental History, which chronicles the rise of cars in North America.

Being anti-car on a visceral level is an easy pattern of thinking that one can fall into. But trying to understands some of the complex reasons for cars success is a necessary step in the process of repositioning it in our transportation system.

“… Car Country refashioned, on a grand scale, both the basic pattern of interaction between people and the environment and fundamental structure and composition of the nation’s ecosystems.

Almost from the beginning, these changes inspired a legion of vociferous critics. By the time full-blown discontent with America’s car culture and its destructive environmental effect finally percolate up into national politics in the 1060s and 1970s, however, patterns of sprawling, low-density development had already become thoroughly ingrained in the American political economy. Moreover, Car Country’s critics too often focused on particular problems–factory pollution, tailpipe emissions, roadside eyes sores, suburban “boxes made of ticky tacky”, the loss of public “open space” and “pristine wilderness”-without understanding the broader, interconnected forces at work that continued to roll out new car-dependent communities year after year. Environmentalists secured new regulations that limited some of low-density sprawl’s more damaging environmental effects, but they failed to stop sprawl itself or the engines driving its expansion. The overwhelming tendency among critics, with a few important exceptions, has been to focus on cars rather than roads and on the behaviour of drivers rather than the powerful forces shaping American land-use patterns. “

Car Country: An Environmental History

Christopher W. Wells, 2012

University of Washington Press